To combat climate change, reduce air pollution, and establish greater energy independence, China has been pushing hard for a nation-wide transition to renewable energy, and is now home to the world’s largest market for wind-generated electricity. The installed capacity for wind generation in China accounts for over one third of the global total. Yet a paper recently published in Nature Scientific Reports and covered by the Washington Post found that climate change might be threatening wind power — one of the very strategies that countries are relying on to help them achieve the goal set forth in the Paris Agreement of keeping global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius.

The Harvard-China Project sat down with one of the co-authors of the paper, Ph.D. student Peter Sherman, to discuss his team’s findings. This article also appeared on the China Project's blog platform, Medium. It was also translated into Chinese on the Medium site.

Peter, you had a paper that was published in Nature Scientific Reports. Can you tell us more about the paper? What is the topic of investigation?

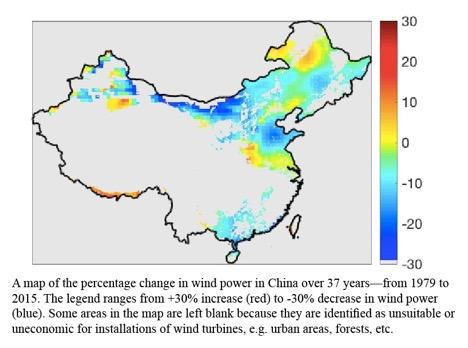

Under the supervision of Professor [Mike] McElroy and Xinyu [Chen], we looked at wind variability in China over the past 37 years from 1979 to 2015. We used a NASA dataset, which combines model data with observations from stations, to see how wind has varied over these years and how it could affect wind power.

What did you find? What are the results?

We found that there is a declining trend in wind speed over the past 37 years, particularly over the regions where a lot of wind farms in China already exist, mainly Western Inner Mongolia and northern China, where there are not only high wind speeds, but also environments that are suitable for installing wind turbines — so regions with the proper geographical features. We found a decrease in wind speed in these regions and it correlates really strongly with rising regional and global surface temperatures, which makes physical sense. We conclude that because there were these rising surface temperatures and decreasing wind speed trend, climate change probably had a pretty significant contribution to the decreasing trend and it could continue in the future.

Can you explain to us briefly how rising surface temperatures affect wind speed?

Basically, winds are formed by pressure differences. If there is high pressure in one area and low pressure in another, it’s going to form wind. A lot of this is due to the temperature difference between land and sea. If temperatures are increasing over land more than they are over sea, then we would expect this temperature difference to shrink and wind speed to decrease along with that. That’s what we think we are seeing here.

How do you think your finding might affect the planning of wind installations and the energy transition in China?

I don’t think it should affect the planning. While these decreases in wind speed may be happening, wind power is still very important and should become a more dominant source of energy in the future, because coal, we know, is not good for the environment. So while there may be decreasing potential for wind power, it’s still very useful. An area of concern that China has is wind curtailment. Wind power is a variable source; when it’s really windy and we don’t use all the wind power, we don’t have any way of storing that wind, so it’s being wasted. What China, in particular, needs to work on is to develop some kind of storage, like a battery, in order to be able to store the extra wind power that is not being used.

Are the results what you expected? Is there anything surprising?

There have been some other papers in the past that have talked about the decreasing wind potential in China, but we were particularly surprised by how strong the decrease was for these areas where there (is? was?) great potential for wind — the greatest declines were actually in those areas, so that was pretty surprising for us.

Are there any future questions that your research raised?

What we are planning on doing now is we are going to look at climate models that project how wind speeds are going to change in the future to see if those models also demonstrate this declining wind speed trend and if that could affect wind power in China.

For some of our readers who might know little about this topic but are very concerned about the environment and climate change in general, especially with all these ongoing discussions about energy transition that is necessary to combat climate change, what is the one thing you want them to take away from this paper?

That climate change has broad implications for the energy system as a whole. Wind power is obviously an important step going forward in terms of what we should do to protect the environment, and yet even something like this is affected by climate change. It is important to bear this in mind in the future.

How did you get involved in this research?

In the winter of my junior year in college, I was looking for research projects to do over the summer. I looked up on Google the various professors who do research that I am interested in. I found Prof. [Mike] McElroy and reached out to him. He offered me a research assistant position with the Harvard-China Project over the summer, and I was really interested in it, so I took it right away. It worked out very well. That’s also how I met Xinyu [Chen], who is a postdoc at the China Project.

How do you find the transition from being a research assistant at Harvard-China Project to being a Ph.D. student at Harvard? What made you decide to come to Harvard to get a Ph.D.?

I found the transition very easy: it was basically doing the same sort work that I was doing over the summer. I have always planned on going to Harvard, and I think my work with Mike and Xinyu really confirmed that. It made me realize how collaborative the environment is here; everyone is willing to help with your work and talk to you — I was really surprised by that. When I was applying for graduate schools, there were a few other options I had, but I just felt that the environment here was so collaborative and helpful that I felt it was perfect for me.

Paper cited:

Peter Sherman, Xinyu Chen, and Michael B. McElroy. 2017. “Wind-generated electricity in China: Decreasing potential, inter-annual variability, and association with climate change.” Scientific Reports 7.

Peter Sherman is currently pursuing his Ph.D. degree in Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University. He received his undergraduate degree in physics from Imperial College London, U.K.. He is interested in a variety of topics, particularly green technology and how weather might affect it, and climate models in general.

This article also appeared on the China Project's blog platform, Medium: https://medium.com/@harvardchina/climate-change-might-be-a-threat-to-wind-power-f17233f4a616

It was also translated into Chinese on the Medium site.